Wanderful Loves

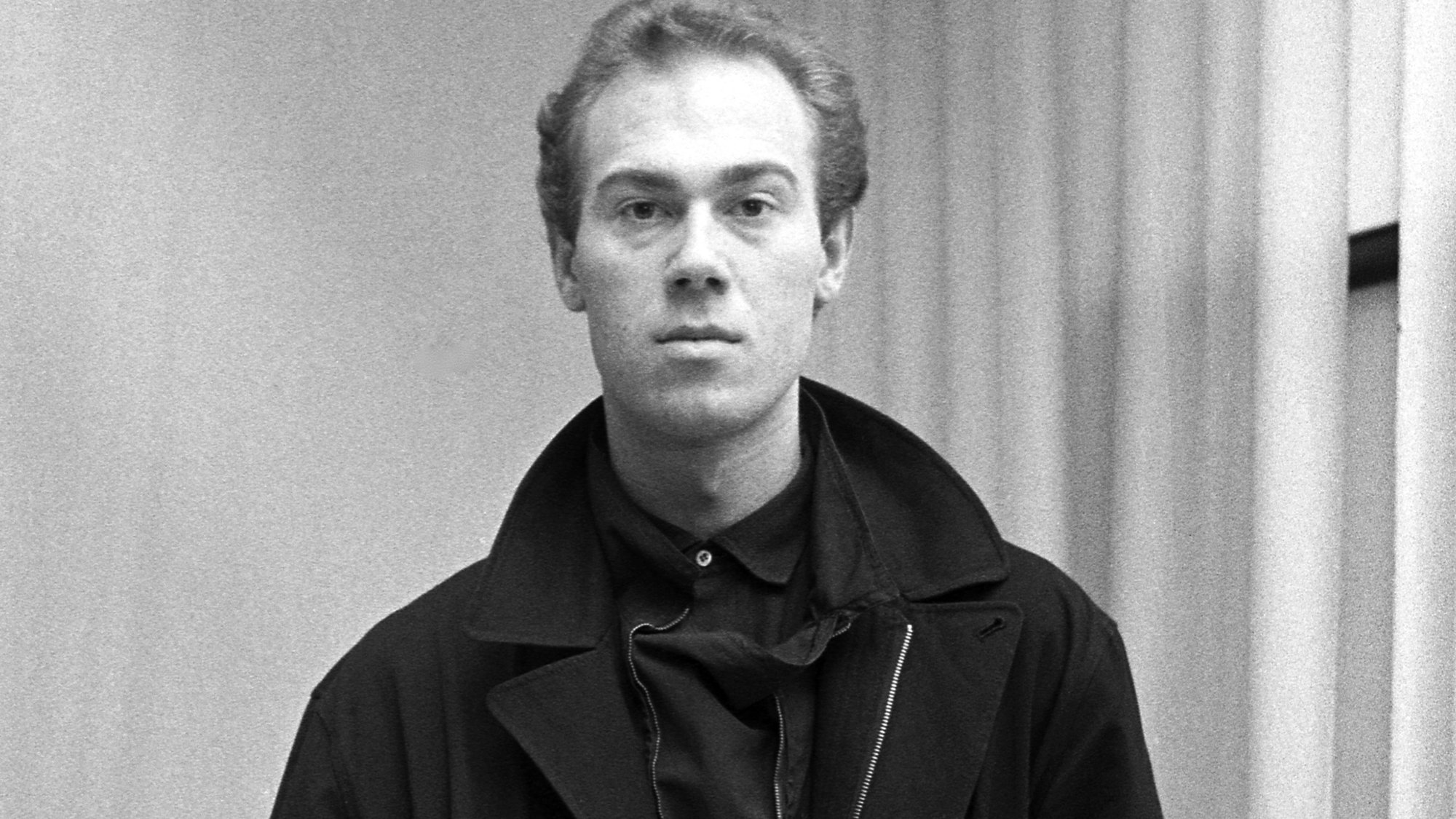

After graduating from the Antwerp Academy in 1982, fashion entrepreneur Dirk Bikkembergs first won acclaim as one of the group of experimental designers that came to be known as the ‘Antwerp Six’. From his earliest menswear collections – celebrated for their innovative utilitarian style – Bikkembergs found a following among the global avant-garde.

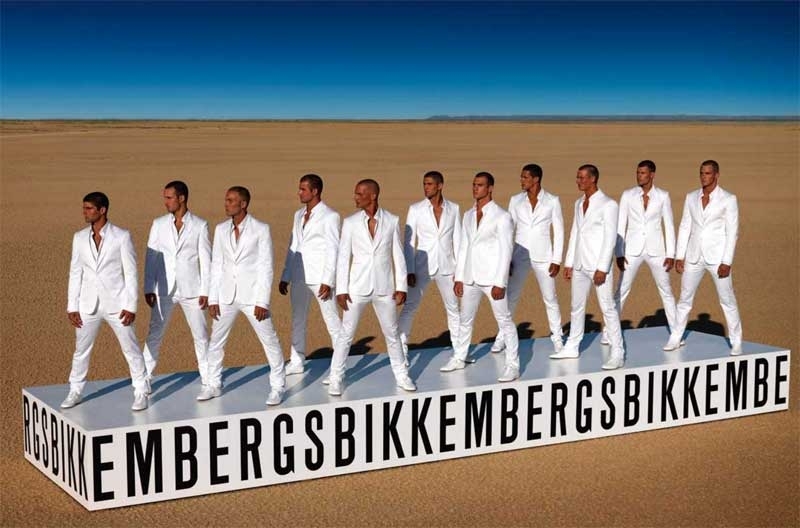

In 1999, Bikkembergs took his eponymous company in a radical new direction, infamously placing a football on the table during a meeting to announce a change of focus, from the catwalks of Paris to the stadia of Italy. Dirk Bikkembergs clothing and footwear became synonymous with sport, and football in particular.

From 2005, the Bikkembergs label sponsored a local Italian football team, FC Fossombrone. The team became the ‘face’ of the Bikkembergs Sport brand, and were dressed in designer football boots and ‘sports couture’ suits and strips for ad campaigns and sporting fixtures alike. In 2011, Dirk Bikkembergs sold his eponymous brand, which today is majority-owned by the Chinese group Canudilo.

CLUBBING

Hettie Judah: Can you explain to me what your connection is to Limburg?

Dirk Bikkembergs: I never actually lived in Limburg. My dad was from there but he met my mum while he was in the army in Germany (she is German). I grew up in Germany and went to Antwerp when I was eighteen to go to the Academy of Fine Arts. While I was a teenager we visited my grandmother and my father’s brother in Limburg regularly. My cousin Mady got the fashion bug into my brain. So I just spent weekends in Limburg, but the club scene from there was very important for me, as I went out clubbing with Mady every evening I was there. So we knew all the important clubs in the province inside out. That’s probably my strongest connection to Limburg.

HJ: Are there elements of your own background and childhood that you can identify as having fed through into your later work?

DB: When I arrived at the Academy of Fine Arts, I came under the responsibility of [Mary] Prijot, the teacher, and I was sitting with Dries [Van Noten], Ann [Demeulemeester], Dirk [Van Saene], Walter [Van Beirendonck], Marina [Yee] and Martin [Margiela] in the same room: that’s how it all started.

HJ: Is there a sense of roots that come out in anything that you’ve done?

DB: No, not at all.

HJ: Do you feel like you are a European?

DB: This is much better, but I would even go further: worldwide!

GEOGRAPHICAL IDENTITY

HJ: Looking at the global fashion industry now, do you think a sense of origin and sense of place – a geographical identity – is important?

DB: The moment the Internet broke through, that changed everything. Communication via the Internet and all these other systems is not the same as it was before. Before it was very local – it was Milan, it was London – now, everybody knows how to communicate quickly. Before you know it, you are looking at the work of a Brazilian designer without even realising it. So, roots? I think they become less and less important.

HJ: Even in your earlier collections, though – when you were creating pieces that were more influenced by military garb, for example – was there not a sense of origin?

DB: I was thinking about this question of what has actually influenced me – because when I went to school in Antwerp, I knew the name Yves Saint Laurent, and I knew the name Christian Dior, but that was all I knew: I didn’t even really know what they did. So in some respect there was absolutely no fashion background whatsoever before I stepped into that school, which means that everything I did from day one – what they showed me there, what I heard from my colleagues, what we were talking about – was the starting line. I remember a GQ magazine cover in, I guess, the 1980s. It was a picture by Bruce Weber. It was just a guy, a typical American guy with short hair and he had Ray-Ban Wayfarers on and I remember I was just so struck by it. I’m a very visual person. Everything I like, everything around me, has to be beautiful. My eyes are always chasing beauty.

HJ: So not club style or anything like that?

DB: No, no, no. I was much more Olympic. I could say my influence might have been Nike, Bruce Weber and Giorgio Armani; put them in a blender and this was my vision. I couldn’t work at that time with Nike because it was really sport-sport. Armani for me was spot-on at the time. And then obviously, when you saw Armani campaigns done by Herb Ritts or Bruce Weber – it was apocalyptic for me! As far as I’m concerned, these guys created my rules.

HJ: And did you draw anything from vernacular style, from people on the streets?

DB: I remember one of my first interviews was ‘what is your perfect outfit for a man?’ I was at school still, in the final year, and I said ‘A white Hanes T-Shirt, a 501 from Levis and a pair of All Stars’, and if you asked me today, I would tell you exactly the same thing, just perhaps with other labels, but in some respects it didn’t change. I always saw my vision there.

ANN & DRIES

HJ: Is that partly because your interest is with the body in the clothes rather than the clothes themselves?

DB: Of course! But I always admired people who could live with strong willpower and self-discipline. I was always fascinated. People in the fashion business don’t realise how much passion and compassion it takes to be a sportsman. They never understood that vision.

HJ: So your understanding of fashion all came from the education that you got?

DB: I think Antwerp was a moment in time and the people who we were with. In some respects, we handed it to each other; the taste or the vision was very personal for each of us. Everybody had his own way of seeing things. I could see it in front of me when everyone was sitting there: Ann was thinking one way, Dries another, Martin another and so on. I remember all of us were exactly like we are today, which is great, because nobody has been over-influenced or become someone else.

HJ: At the time when you all came out of the Academy, your generation had the support of the Golden Spindle Awards, which nowadays people view as having been very important. Do you look back and see this support as being a big deal?

DB: I don’t know. It was nice at the time. But it was perhaps just another ‘electric shock’ to say ‘okay, keep it up!’ With or without it, I would have done the same thing afterwards.

NY PARIS

HJ: Do you think that your career would have been very different if you had come from a fashion ‘capital’ such as Paris or New York?

DB: Basically, whether in London or New York or wherever, at that moment people were looking at pictures by Bruce Weber, I would have gone after the same thing, I think. I don’t think it would have changed anything in my vision of what I liked, no.

HJ: I always think that the designers that come out of Antwerp – not just in your time, but in general – are very good at presenting their work as a complete story. It’s a bit like pitching a movie.

DB: In the years that we were at school, every end of year we had to give our presentation. I’d always watch these presentations and think about what I liked and what I wanted to do better. When we came out of school and there was no competition we were always very on the ball, and able to tell a strong story in 30 seconds.

HJ: Because you never had a sense of entitlement, a belief that someone would listen to you come what may?

DB: You have to consider that at that time, there was a lot of hunger in fashion. People really wanted things to happen. It’s not like that today anymore – who’s still hungry? Everybody has everything! I think, to be honest with you, that we lived through the most amazing time in fashion that there has ever been, in the 1980s, 1990s. By 2000, it was already over for me.

HJ: In the early days you were making high fashion collections that were a lot to do with construction and detailing and so on. Do you think that people still understand those kinds of garments?

DB: Do you think they don’t make the effort to think it through? I don’t think that people sit down and start analysing a jacket. I analysed way too much, everything, which wasn’t necessary. People look at a global movie in a blink of an eye – you either catch their attention or you don’t.

SATISFACTION

HJ: I know there was this point for you when you felt you were done with the whole fashion carousel…

DB: I have never ever been a person who was really after the fashion thing – it was just a process. But when the day came that I put the football on the table, this was where I was meant to be: I was meant to be on the blacklist of Nike, I was meant to be on the blacklist of Adidas. This was what I was meant to do with my life.

HJ: So you’re absolutely interested in mass fashion rather than something more rarefied?

DB: I like to reach an audience that is not interested in fashion for the sake of fashion. So when I did my shoes and saw regular guys who were not interested in fashion wearing them, that was satisfaction for me. To satisfy Anna Wintour is one thing. But to have a guy that has no idea and he goes in a shop and opens his wallet and he pays €150 for a pair of shoes or a jacket, and you see him in the street, and then you turn around, and there’s another one, and another one…

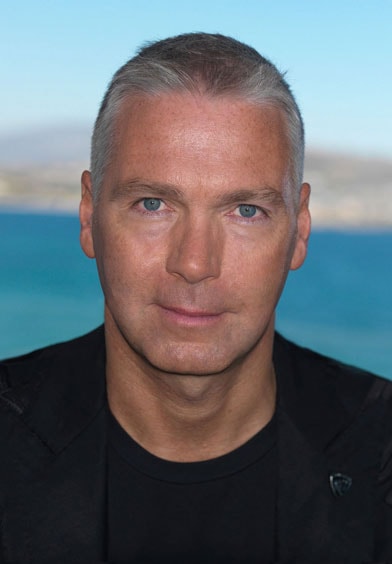

HJ: Have you now stepped back from doing anything with fashion?

DB: I sold my company in 2010, and I think 2011 was the last time I took a fashion magazine in my hands. I don’t feel fashion anymore. I love, for example, Uniqlo. I love these kinds of things because I think they are ‘just right’. And at the same time, fashion became so expensive, and that means that the niche that it was in the 1980s or 1990s, became even smaller. In the 1980s, if a woman really wanted a Thierry Mugler tailleur, she could afford it. Today you have to be a Rockefeller. The whole market has shifted: it’s just about money. It’s about making business turnover grow every year.

ENJOYING LIFE

What they sell you today is completely other-world – I don’t feel it anymore. I liked the period that I started in. If you speak to an 18-year-old at Central Saint Martins, they will probably say something different: that now is the moment, which I can understand. But for me, it was perfectly fine in our day because we were all hungry for fashion. Every six months we’d take two old cars from Antwerp and drive to Paris for the shows. We had fake tickets because it was a fight to get in. It’s not like that anymore: today you can click on your screen and watch the fashion shows in your bath. It’s not my thing.

Now I’m enjoying my life: I only do from morning to evening what I really want to. I worked non-stop for thirty years, but I did it with love and if I lived my life over I would do it again. If I had felt that what I was doing would lead to something that had an impact, I would probably have continued, but I could see that it wasn’t. The fashion industry today is completely ruthless; it has nothing to do with beauty. It’s just about turnover. There’s no room for love.